In my last quarterly economics report I said, “GDP is growing at about a healthy 3%, unemployment is relatively low, inflation looks like it is headed for 2%, interest rates are expected to continue to decline and consumer sentiment appears relatively strong”. Well, I was partially right and partially wrong, which is about average for economic forecasting. In fact, in an article released by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank in December of 2024 they stated that, based on their research, the historic forecast performance for professional forecasters revealed that they were correct in forecasting GDP growth, unemployment rates and 10 year treasury yields less than half the time and correct in forecasting CPI inflation 56% of the time.

What was correct: GDP is healthy, unemployment is low, and consumer sentiment is strong.

- After a slow start to GDP growth in the first quarter of 2024 at 1.6%, the rate of increase climbed sharply to 3% in Q2, 2.8% in Q3 and the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow (an ongoing estimate of Gross National Product but not an official estimate) estimate for Q4 is 3%.

- Unemployment remains relatively low, the JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary) report throughout 2024 remained stable as hires and quits were generally in balance.

- Mastercard reports that 2024 holiday sales grew by 3.8% which represents real growth above the rate of inflation. As of January 17th, with 9% of S&P 500 companies reporting, 79% have had positive EPS (earnings per share) surprises and 67% have had positive revenue growth surprises according to Factset. Factset further reports that “On December 31st, the estimated (YOY) earnings growth rate for the S&P 500 for Q4 2024 was 11.9%. While early in the reporting season, 2024 is looking like a good earnings year for U.S. companies.

There has been a shift, though, with regard to expectations for inflation and interest rates.

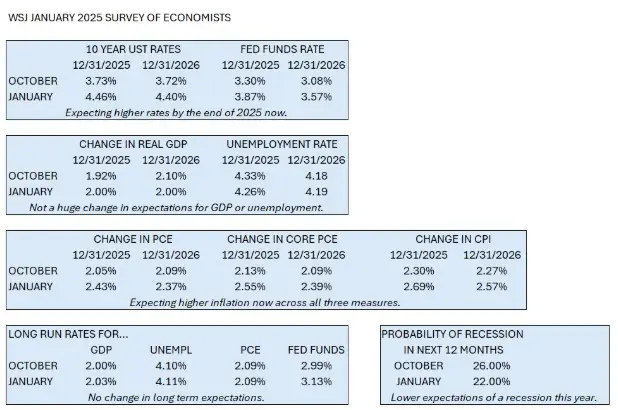

As you know, one data set I follow regularly is the Wall Street Journal quarterly survey of economists (even though we now know they are only right half the time). The January survey was released on the 20th and I compared it to the October survey. Something has happened since the November election. The comparison is below.

As you can see in this comparison, there has been a significant shift in the outlook for interest rates and inflation over the next two years although the long term run rates are essentially unchanged.

So, what drives this change? While I think the U.S. economy enters 2025 in a healthy position, three factors have our attention: an unexpected December jump in PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation), the impact of potentially steep and broadly applied tariffs and the impact of aggressive enforcement of immigration laws.

Inflation turned back upward in December

Year Over Year Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) in December was 2.82%, which was down from 3.22% in 2023. However, this was a jump from the range of 2.1% to 2.4% reported August through November and was about 0.4% above expectations. After this report, the market called into question the likelihood of the Federal Reserve continuing rate reductions at the then current pace. Instead of continuing a trend downward toward 2.0%, the Fed’s inflation target, PCE, turned upward in December, surprising economists and causing an adjustment to inflation and interest rate expectations.

Tariffs are coming (maybe) and they may be inflationary (but may not impact GDP)

In my research for this article I was only able to find one economist that argues that tariffs are not inflationary. That was Joseph Lavorgna who served as the Chief Economist for the National Economic Council during the first Trump administration.

Tariffs are taxes. They are a levy applied to goods and services that are imported into a country. Tariffs are not paid by the country exporting the goods and services or by the sellers. They are payments collected by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, at U.S. ports of entry, and they are paid by the U.S. entity importing the goods and services. If you are an importer of goods and services that are subject to tariffs, you write the check to the U.S. C&BP. Tariffs make imported goods more expensive than they would otherwise be. While it is broadly accepted that tariffs raise prices, the overall impact on an economy-wide inflation rate appears to be low. Historically, sellers have sometimes lowered their prices to remain competitive, importers absorbed a portion of the tariff and consumers made up the difference by paying higher prices.

The Tax Foundation reported in 2021 that the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimated that “The first three tranches of tariffs on Chinese goods, (implemented by President Trump), raised economy-wide consumer prices by 0.1%”. This study also estimated that tariffs of 25% on all Chinese imports would raise consumer prices by 0.3 percentage points. (Tax Foundation – December 15, 2021)

Let’s look at the tariff banter during President Trump’s trade war of 2018 and 2019.

– July 6, 2018: U.S. threatens to levy tariffs on $300 Billion of Chinese imports. S&P goes up 10 points.

– July 20, 2018: U.S. affirms plan to levy tariffs on $500 Billion of Chinese imports. S&P drops 10 points.

– August 1, 2018: U.S. considers increasing tariffs on $200 Billion of Chinese goods from 10% to 25%. S&P goes up 14 points.

– August 8, 2019: U.S. threatens to impose a 10% tariff on an additional $200 Billion of Chinese goods if China retaliates. S&P drops 4 points.

– May 10, 2019: U.S. announces it will raise tariffs on $200 Billion of Chinese goods from 10% to 25% with a threat of an additional 25% on $325 Billion of Chinese goods. S&P drops 70 points.

– July 5, 2019: U.S. threatens China with tariffs on $500 Billion of imports—essentially all Chinese imports to the U.S. S&P drops 5 points.

– July 20, 2019: U.S. announces a 10% tariff on all Chinese imports. S&P goes up 9 points.

– August 1, 2019: U.S. announces a tariff increase from 10% to 25% on $200 Billion of Chinese goods. This represents a reduction from a previous announced rate of 25%. S&P drops 19 points.

– August 13, 2019: U.S. announces the delay of the above implementation from September 1 to December 15. S&P goes up 44 points.

– August 23, 2019: China announces a 5% to 10% tariff on $75 Billion of U.S. goods imported into China to begin September 1 and expire on December 15, and also to resume tariffs on cars and parts imported from the U.S. which were suspended earlier in 2019. S&P drops 75 points.

– October 15, 2019: U.S. postpones a scheduled increase in tariffs from 25% to 30% on $250 Billion of Chinese goods. S&P goes up one point.

– December 16, 2019: U.S. postpones indefinitely tariffs covering $160 Billion in Chinese goods and a reduction in tariffs from 15% to 7.5% on an additional $120 Billion in Chinese goods. S&P drops 36 points.

– February 20, 2020: U.S. reduces tariffs on $120 Billion Chinese goods to 7.5%. China reduces tariffs on $75 Billion U.S. goods from 5% to 2.5%. S&P drops 36 points.

– August 13, 2020: U.S. reimposes tariff on $2.5 Billion import of Canadian aluminum. Canada to impose retaliatory tariffs. S&P remains flat.

– September 18, 2020: U.S. eliminates tariff on $2.5 Billion of Canadian aluminum imposed on August 16, 2020 to avoid Canadian retaliation S&P drops 38 points.

What does all of this tell us? It tells me that the imposition of tariffs is very fluid. During this period, we did not see the imposition of tariffs that remained unchanged for extended periods of time. Rates were constantly changing. I question how we can accurately measure the economic impact of the trade war when we continuously impose, remove, increase and decrease tariffs. Especially when as we have seen in some cases, that the imposing country states that the tariff will be in place for 90 days. Importers would certainly time their purchases.

I can tell you that the Bureau of Economic Analysis in the Department of Commerce reports that U.S. GDP increased 2.9% in 2018, 2.2% in 2019 and declined 3.5% in 2020 due to Covid-19. The S&P 500 fell 6.2% in 2018 and grew 29% in 2019 and 16.3% in 2020. The decline in the S&P 500 in 2018 while GDP was growing is attributed to the Fed hiking interest rates and uncertainty of the impact of tariffs.

My conclusion on tariffs is that they will create a headwind to the Fed’s fight against inflation, resulting in rates staying higher for longer than they otherwise would have without new tariffs, but their impact on GDP growth will be minimal.

A shrinking labor force may be inflationary (and could impact GDP)

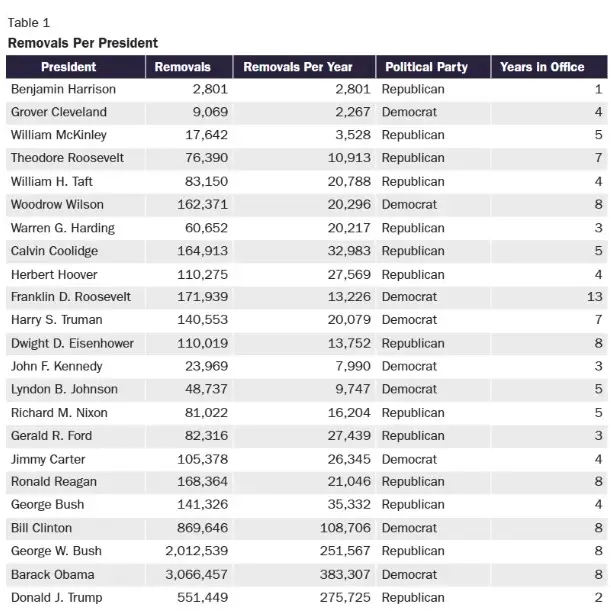

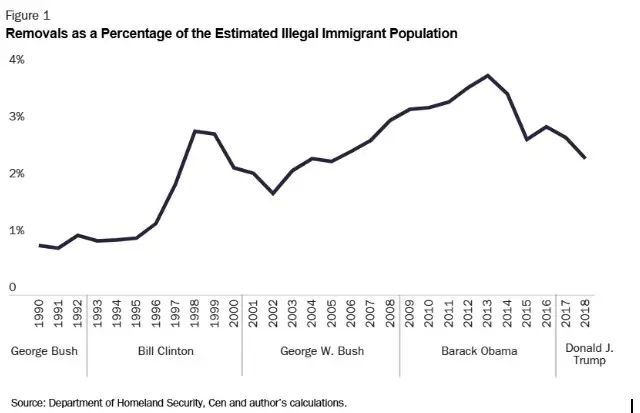

Immigration enforcement’s economic impact has been much harder for me to get my mind around. Deportation of unauthorized immigrants is not a new undertaking for the U.S. We have a long history of attempting mass deportation. “Operation Wetback” (it was really called that) was an Eisenhower era action in which 1,074,000 unauthorized immigrants were “returned” to their country of origin between June and October, 1954. What I don’t know is how many unauthorized immigrants were in the US at that time and therefore what percentage were removed. The number of removals began increasing in the last half of the Clinton administration and has continued to grow through the Biden administration. See Table 1 below (this is from 2019, so doesn’t reflect the full first term of President Trump, which was 1.5 million, and doesn’t include President Biden’s term, which is also expected to be around 1.5 million). Removals as a percentage of total unauthorized immigrants peaked during the Obama administration. See Figure 1 below.

Source: Cato at Liberty – September 16, 2019

But what was the economic impact of these removals? I found this very hard to nail down. Obviously, the difference between removing 4% of unauthorized immigrants (the peak to date) versus 100% (the Trump plan) is dramatic. Most articles forecast a decline in GDP, a rise in inflation, higher unemployment and the loss of jobs by U.S. born workers. The forecasted numbers range from small to large depending which side of the argument is doing the forecasting. The facts are that during this period of increased immigration enforcement since 1990, we have experienced three recessions, the dot-com bubble in 2001, the Great Recession in 2007-2009 and the Covid-19 recession in 2020. None of these were the result of deportation. Other than those periods, the U.S. economy has been healthy.

President Trump’s second initiative having the potential for major economic impact is immigration law enforcement. The American immigration Council reports that in 2022 there were 11 million immigrants lacking permanent legal status and that this number has increased by 2.3 million by year end 2024. If accurate we have 13.3 million undocumented immigrant residents. Their estimate of the cost of removing these immigrants over the next ten years to be just under $1 Billion. They report that there are currently 1.9 million prisoners incarcerated in all federal and state prisons and all county and city jails. They predict the manpower cost and physical facilities needed to accomplish the task of removing 13.3 million people will be significant.

What will be the economic impact? What’s $1 Billion over 10 years in relation to the overall U.S. budget? Not even a decimal place. But the Council puts total annual federal taxes paid by undocumented immigrants at $468 Billion, state and local taxes at $293 Billion, social security payments at $22.6 Billion and medicare at $5.7 Billion. That totals $789 Billion. Of course, if all these jobs are replaced, revenue should not be impacted.

Absent hard data, I can’t reach any conclusions as to the economic impact of President Trump’s immigration enforcement plans. I will continue to research and follow the news and if some clarity appears I will report back to you.

As I acknowledged in my opening, economic forecasting is not terribly reliable. There is no Hall of Fame for forecasters because it would be empty. Still, it can be telling to note the trends among a group of forecasters, which is why I like the WSJ Survey (73 economists are surveyed). A change like we see now in their expectations for inflation and interest rates is noteworthy. While higher inflation and interest rates are not welcome for consumers or borrowers, the impact on the economy overall and on U.S. companies could be mitigated by consumer confidence and earnings growth. As I have said many times, I wouldn’t bet against the U.S. economy.

This material is for general information only and is not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. There is no assurance that the views or strategies discussed are suitable for all investors or will yield positive outcomes. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Together Planning has a reasonable belief that this marketing does not include any false or material misleading statements or omissions of facts regarding services, investments, or client experiences. Together Planning has a reasonable belief that the content will not cause an untrue or misleading implication regarding the adviser’s services, investments, or client experiences. Any economic forecasts set forth may not develop as predicted and are subject to change. Any references to markets, asset classes, and sectors are generally regarding the corresponding market index. Indexes are unmanaged statistical composites and cannot be invested into directly. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any investment and do not reflect fees, expenses, or sales charges. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

Market projections or investment growth, including those in examples, are not indicative of future results, should not be considered specific investment advice, do not take into consideration your specific situation, and do not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any securities or investment strategies. Investments involve risk, including changes in market conditions, and are not guaranteed. Be sure to consult with a qualified financial advisor and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Together Planning is a SEC registered investment advisor.